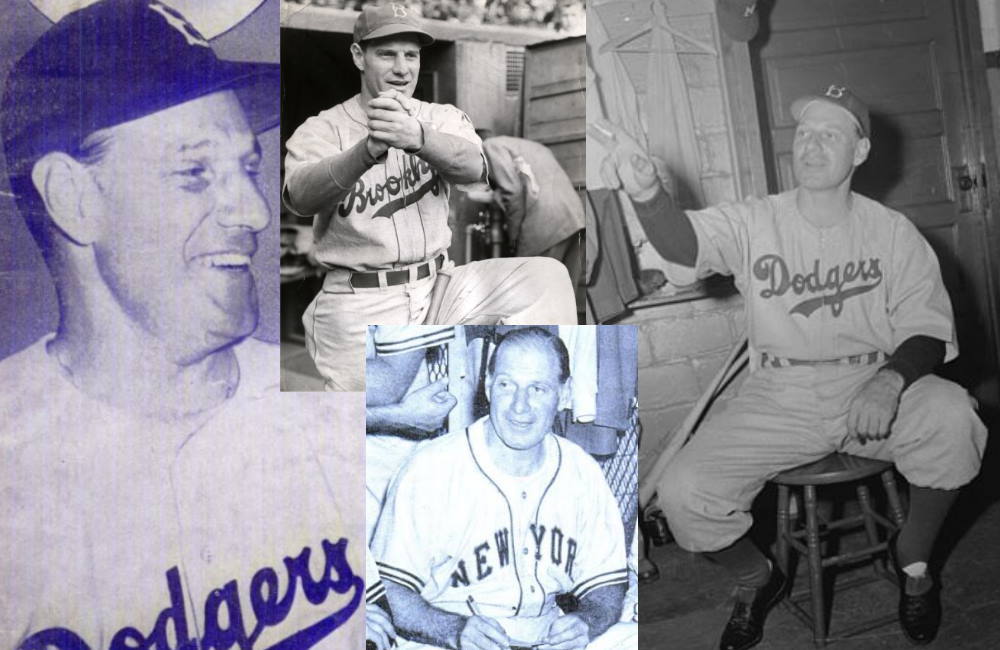

As both a player and manager, Leo Durocher is remembered as a fierce competitor who became a champion. He won 2,008 games as a manager with four different teams, including winning the 1954 World Series as skipper of the New York Giants.

He’s also remembered because he simply could not stop talking, arguing with umpires, players, team owners, even teachers as a kid. He’s a person who truly earned his nickname as “The Lip.” Umpires ejected him 95 times during his time as a manager. But he won a lot and still ranks as the 11th most winning manager in MLB history. He became a member of the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1994, three years after his death.

Durocher also played a key supporting role in the integration of MLB in the 1940s as a manager with the Brooklyn Dodgers.

Leo Durocher’s Early Life

Durocher came from a family of French Canadians. Born in West Springfield, Massachusetts, Durocher was the youngest of four sons. His parents had immigrated to the U.S. from Quebec. He grew up in a household where everyone spoke French, and actually started grade school without speaking any English. That’s an interesting little detail for a man who later used the English language more than most.

He made it through grammar school but shortly after starting at Springfield Technical High School, he got into a fight with a math teacher and never returned to school. It was a sign of things to come.

He played baseball in the Catholic Junior League and soon made a name for himself locally as a ballplayer. He became a semi-professional athlete before getting his chance in the majors.

Leo Durocher’s Early Career

Durocher got his chance to take a shot at the big leagues when he played with the Hartford Senators in the Eastern League in 1925. The New York Yankees had scouted him and recommended him to the Senators. He had trouble at the plate (he never became a great hitter) but was a slick-fielding shortstop already at the age of 19.

He played two more seasons in the minors with the Atlanta Crackers in 1926 and St. Paul Saints in 1927. The Yankees called him up in 1928. At the age of 22, he made 329 plate appearances, hitting .270 and scoring 46 runs. The 1928 Yankees team featured nine future Hall of Famers: Durocher, Earle Combs, Lou Gehrig, Tony Lazzeri, Babe Ruth, Bill Dickey, Waite Hoyt, Herb Pennock, and Stan Coveleski. The team won that year’s World Series.

Durocher had already become famous at a young age, playing with some of the best players ever assembled for one team. He also had developed a well-earned reputation for being argumentative and for living an expensive lifestyle even if he couldn’t always afford it.

The Yankees management, unhappy with Durocher’s behavior and also unwilling to give him the raise he wanted, traded him to the Cincinnati Reds in 1930. He later became a member of the St. Louis Cardinals known as the Gashouse Gang, winning another World Series in 1934.

He joined the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1938, and became the Dodgers’ player-manager in 1939. He quickly turned around a franchise that had posted losing records for six straight seasons. In 1941, the Durocher-led Dodgers finished 100-54 and won the NL pennant.

Nice Guys Finish Last

Over the years, Durocher became known for many reasons both on and off the field. On the field, the most enduring image of Durocher is him standing toe-to-toe with an umpire. Or, better yet, kicking dirt on the umpire’s shoes. He also was known for having his pitchers intentionally hit batters and famously said that “nice guys finish last” when describing the managerial style of some of his contemporaries.

Off the field, he hung out with actors, pool hustlers (he was good at pool, himself) and some shady underworld characters. In 1947, NL Commissioner Happy Chandler suspended Durocher for a year due to an “accumulation of unpleasant incidents” which included accusations of associating with gamblers, according to the Hall of Fame.

His personal life kept him in the tabloids, as well. He married and divorced four different women. He spent much of his life mired in debt. He had fights with fans, women, angry husbands, fathers and boyfriends. Through it all, Durocher loved to talk. He reportedly drove some of his teammates crazy, including Babe Ruth with the Yankees. As a way of razzing him, Ruth nicknamed the shortstop the “All-American Out” because of his difficulties at the plate (Durocher hit .247 over his 17-year career).

But Durocher also publicly backed Jackie Robinson when he broke baseball’s infamous color line, joining the Dodgers in 1947. He admired Robinson’s hustle. He famously said: “I do not care if the guy is yellow or black, or if he has stripes like a (expletive) zebra. I’m the manager of this team, and I say he plays. What’s more, I say he can make us all rich. And if any of you cannot use the money, I will see that you are all traded.”

In 1948, Durocher shocked the Dodgers faithful by leaving Brooklyn to manage the Giants. He stayed in New York through the 1955 season, winning the World Series in 1954. He later managed the Chicago Cubs from 1966 to 1972 (he was fired midway through the 1972 season) and the Houston Astros in 1972 and 1973. The Astros finished 1973 with an 82-80 record.

Durocher retired with a winning record for all four clubs he managed. After his retirement, Durocher wrote a famous memoir, “Nice Guys Finish Last.” Throughout his career, he also appeared on many television shows, mostly playing himself, including episodes of “The Beverly Hillbillies,” “Mr. Ed” and “The Munsters.”

He died, at the age of 86, in 1991 in Palm Springs, California.

Leave A Comment