No one knows exactly how fast Amos Rusie threw his fastball because he played long before the invention of radar guns. However, baseball officials ended up moving the pitching mound farther from home plate because of him. And Rusie also once hit a player on the head and knocked him out for four days. So, yes, probably pretty darn fast.

The Hoosier Thunderbolt had a beast of an arm, but he also had bad control, which is why he led the league in both strikeouts and walks. He led the National League in strikeouts for five seasons, but also holds the all-time record for most walks in a single season.

Amos Rusie’s Early Life and Minor League Career

Amos Wilson Rusie was born in 1871 in Mooresville, Indiana. His family moved to nearby Indianapolis when he was young. Rusie dropped out of high school at the age of 16 and did various jobs around the city, including work in a factory and as a varnisher in a furniture store. After hours, he played baseball.

While playing in 1888 for a semi pro team called the Sturm Avenue Never Sweats, Rusie shut out the touring teams for the Boston Beaneaters and the Washington Senators. Blown away by this performance, John T. Brush, owner of the Indianapolis Hoosiers, signed Rusie for the 1889 season. Technically speaking, Rusie’s “minor league career” can hardly be called that – he pitched exactly four games for the Burlington Babies before being called up to the Hoosiers.

At the age of 17, Rusie went up to the majors, making his debut in 1889.

Amos Rusie’s Major League Career

Rusie only pitched one year for the Hoosiers, because after the 1889 season, the team folded. After this, Rusie joined the New York Giants, where he played most of his career.

And what a career it was. The Hoosier Thunderbolt earned his nickname from his incredibly fast pitches. They were so fast, in fact, that his catcher wore a sheet of lead, covered with a handkerchief and a sponge, in his glove to cushion the impact. In 1893, partially because of Rusie’s combination of speed and wildness, baseball officials moved the pitching mound from 50 feet away from home plate to 60 feet and six inches, where it remains to this day.

Rusie led the league in strikeouts five times in his 10 seasons, including 341 strikeouts in 1890. But he also led the league in walks five times. He still holds the record for most walks in a season (289, in 1890). In 1897, he accidentally hit future Hall of Famer Hughie Jennings of the Baltimore Orioles on the head, sending him into a coma for four days.

Rusie put together his greatest year in 1894, when he led the National League in wins, ERA, and strikeouts (but also in walks). At the end of the season, he pitched in the first-ever Temple Cup, a short-lived championship series that pitted the winner of the National League against the runner-up. This year, the Orioles won the league, while the Giants finished as runners-up. The Giants ended up sweeping the Orioles. Rusie pitched in Game 1 and Game 3, and only gave up two runs across both games (one of them unearned).

However, Rusie also had a tense relationship with the Giants owner, Andrew Freedman. In 1895, Freedman cut $200 from his $3,000 salary ($100 for apparently being out after curfew once, and $100 for, somehow, “not trying hard enough” as a pitcher). In 1896, Rusie sued Freedman for $5000 and release from his Giants contract. Other National League teams worried that in the ensuing trial, the courts might invalidate the reserve clause. They offered Rusie $5000 to drop the suit. Rusie accepted the money.

His career probably could have lasted many more years, but unfortunately it was cut short in 1898 when Rusie injured his arm during a game making a snap throw to first base. He was never the same again – he even said decades later that it still hurt at times. He was unable to pitch in 1899 and 1900, and for the 1901 season he was traded to Cincinnati for rising star Christy Mathewson. Rusie played only three games with the Reds before retiring.

After Baseball

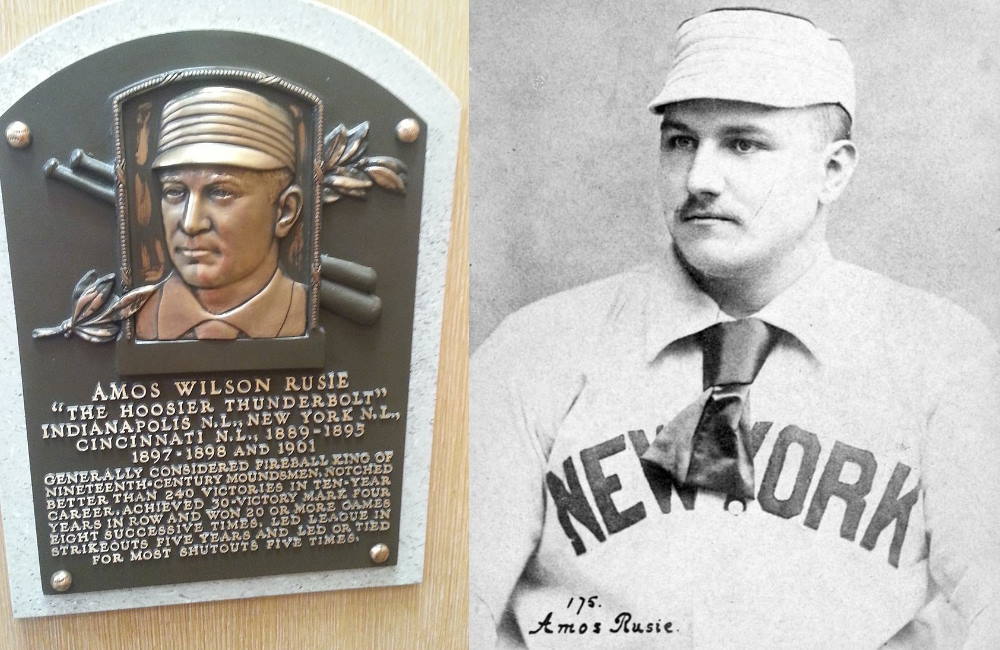

After retiring from baseball, Rusie moved back to Indiana, where he worked various jobs over the years. Eventually, he and his wife bought a farm in Washington, but it failed during the Great Depression and was foreclosed. Upon finding out about this, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer issued a fundraising campaign; they weren’t able to save the farm, but they were able to provide Rusie and his wife with a small house and income for the rest of their lives. Rusie died in 1942, at the age of 71. The Baseball Hall of Fame posthumously inducted Rusie in 1977.

Leave A Comment